Bisley, in the Cotswolds, United Kingdom, is the small family village where I spent long holidays that had a profound impact on my childhood.

The region continues to inspire me in my architectural practice through the sense of harmony it exudes, an interplay of the abundant yet perfectly tamed nature and the man-made constructions that blend in so seamlessly, regardless of their era. The vegetation, like the stone, is lastingly anchored in this place.

But the United Kingdom also has a warm and welcoming culture; there’s always laughter to be heard coming from the fireside of a pub, in spite of the rain outside. It is a welcoming and generous place, that fosters all these interactions and gatherings. Today, whatever the programme, I am determined to create spaces in which every person feels at ease.

Finally, a dual culture means being intrinsically aware of differences and seeking to understand all that is Other. This curiosity has never left me and continues to be the driving force of every one of my encounters.

During my years of studies, I worked for architecture practices in order to learn my trade. In parallel to my studies, I also became a perspectivist. These experiences taught me above all to execute projects designed by others with humility, something that requires an understanding of their vision and their requests. It is at this point that I would like to thank these peers who put their trust in me, taught me such a great deal, confirmed by passion for architecture and made me want to pursue it as a profession. This ability to realise and understand another person’s project is something I encounter today when working with the architects and urban planners who have designed the urban projects in which one of my clusters is located. This bond with my peers is facilitated by a shared understanding of all that is at stake in a city.

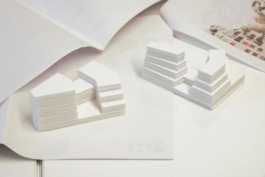

My approach is based on looking for the right solution to a commission, needs that may or may not have been expressed, a context. Much like the natural world, the solution is about fundamentals, far from any gratuitous and needless excess or embellishment. This elementary aspect that I seek out is not cold or austere, rather it is caring, gentle and teeming with diversity, sometimes random but always harmonious. I am therefore attentive to the aesthetic side of my projects, on condition that this form is an expression of the quality of use and function made possible by the project. This approach is particularly perceptible when it comes to the materials used for a façade. I appreciate materials that have a function or use rather than being purely decorative. These are also materials that require real expertise and attention in terms of detail and implementation. Concrete, stone and brick all share this aesthetic of function and expert execution. A building is therefore a sensory object, one to be seen and touched. This project aesthetic is then shared by the person who designs it, executes it and inhabits it on a daily basis.

In reality, designing and executing a project are two distinct areas of expertise requiring different qualities and aptitudes. That said, you can't have one without the other, and understanding a site demands a great deal of user feedback. We design in order build and build in order to design better. My experience of project sites has left me with three key beliefs. The first is that the act of building depends on an ability to anticipate how a building will be realised, in each and every detail. This focus on implementation is something that guides me right from a project’s design phase. The second thing I am sure of is that overseeing a site requires a good understanding of the different stakeholders, a complex yet stimulating network, whereby one needs to know how to establish a dialogue between companies and design offices in order to preserve the quality of the project while working together on the most suitable solutions. Finally, I feel that executing a project means being responsible for the project owner’s interests throughout; ensuring the fundamentals that guided the design have been adhered to, as well as managing the project budget and the timeframe for the site.

I am deeply convinced that a project comes to fruition through teamwork and constant communication with my project owners. In order to forge this trusting relationship, I take a unique working approach to every project, based on listening to and understanding my client’s needs and challenges. This method creates a strong group dynamic through which all our prerequisites are called into question.

This pair formed between the architect and their project owner is at the heart of a much wider world made up of design offices, companies, users, end clients, etc. In order for everyone to play their role, they must all understand each other’s challenges and constraints while promoting dialogue and courtesy.

In order to share this philosophy more widely and contribute to a greater mutual understanding of the roles of project owner and project manager, I became a member of the office and board of directors of the association AMO (Architecture and Project Owners).

The act of building requires us to summarise the needs and constraints of the present, even though the effects of a project will be felt by the generations of the future. The architect therefore has a responsibility in every project that contributes to our future heritage. This issue of a project’s quality and durability guides me in both considerations of current and future uses, as well as a project’s environmental performance. It is not a question of responding to trends or accumulating expensive and soon-to-be obsolete gadgets. On the contrary; it is about revisiting the ancestral construction methods that have been able to meet our evolving needs throughout the ages.

Bisley, in the Cotswolds, United Kingdom, is the small family village where I spent long holidays that had a profound impact on my childhood.

The region continues to inspire me in my architectural practice through the sense of harmony it exudes, an interplay of the abundant yet perfectly tamed nature and the man-made constructions that blend in so seamlessly, regardless of their era. The vegetation, like the stone, is lastingly anchored in this place.

But the United Kingdom also has a warm and welcoming culture; there’s always laughter to be heard coming from the fireside of a pub, in spite of the rain outside. It is a welcoming and generous place, that fosters all these interactions and gatherings. Today, whatever the programme, I am determined to create spaces in which every person feels at ease.

Finally, a dual culture means being intrinsically aware of differences and seeking to understand all that is Other. This curiosity has never left me and continues to be the driving force of every one of my encounters.

During my years of studies, I worked for architecture practices in order to learn my trade. In parallel to my studies, I also became a perspectivist. These experiences taught me above all to execute projects designed by others with humility, something that requires an understanding of their vision and their requests. It is at this point that I would like to thank these peers who put their trust in me, taught me such a great deal, confirmed by passion for architecture and made me want to pursue it as a profession. This ability to realise and understand another person’s project is something I encounter today when working with the architects and urban planners who have designed the urban projects in which one of my clusters is located. This bond with my peers is facilitated by a shared understanding of all that is at stake in a city.

My approach is based on looking for the right solution to a commission, needs that may or may not have been expressed, a context. Much like the natural world, the solution is about fundamentals, far from any gratuitous and needless excess or embellishment. This elementary aspect that I seek out is not cold or austere, rather it is caring, gentle and teeming with diversity, sometimes random but always harmonious. I am therefore attentive to the aesthetic side of my projects, on condition that this form is an expression of the quality of use and function made possible by the project. This approach is particularly perceptible when it comes to the materials used for a façade. I appreciate materials that have a function or use rather than being purely decorative. These are also materials that require real expertise and attention in terms of detail and implementation. Concrete, stone and brick all share this aesthetic of function and expert execution. A building is therefore a sensory object, one to be seen and touched. This project aesthetic is then shared by the person who designs it, executes it and inhabits it on a daily basis.

In reality, designing and executing a project are two distinct areas of expertise requiring different qualities and aptitudes. That said, you can't have one without the other, and understanding a site demands a great deal of user feedback. We design in order build and build in order to design better. My experience of project sites has left me with three key beliefs. The first is that the act of building depends on an ability to anticipate how a building will be realised, in each and every detail. This focus on implementation is something that guides me right from a project’s design phase. The second thing I am sure of is that overseeing a site requires a good understanding of the different stakeholders, a complex yet stimulating network, whereby one needs to know how to establish a dialogue between companies and design offices in order to preserve the quality of the project while working together on the most suitable solutions. Finally, I feel that executing a project means being responsible for the project owner’s interests throughout; ensuring the fundamentals that guided the design have been adhered to, as well as managing the project budget and the timeframe for the site.

I am deeply convinced that a project comes to fruition through teamwork and constant communication with my project owners. In order to forge this trusting relationship, I take a unique working approach to every project, based on listening to and understanding my client’s needs and challenges. This method creates a strong group dynamic through which all our prerequisites are called into question.

This pair formed between the architect and their project owner is at the heart of a much wider world made up of design offices, companies, users, end clients, etc. In order for everyone to play their role, they must all understand each other’s challenges and constraints while promoting dialogue and courtesy.

In order to share this philosophy more widely and contribute to a greater mutual understanding of the roles of project owner and project manager, I became a member of the office and board of directors of the association AMO (Architecture and Project Owners).

The act of building requires us to summarise the needs and constraints of the present, even though the effects of a project will be felt by the generations of the future. The architect therefore has a responsibility in every project that contributes to our future heritage. This issue of a project’s quality and durability guides me in both considerations of current and future uses, as well as a project’s environmental performance. It is not a question of responding to trends or accumulating expensive and soon-to-be obsolete gadgets. On the contrary; it is about revisiting the ancestral construction methods that have been able to meet our evolving needs throughout the ages.